Trust the Process

Drugs became a leading cause of incarceration in the United States starting in the 1970s, when President Richard Nixon began what has been characterized as a politically motivated, racist effort to criminalize substance use. In the ensuing decades, stringent drug policies and the War on Drugs have helped cause the U.S. prison population to swell to more than two million, including a disproportionate number of people of color. Drug-related arrests continue to be prominent in the U.S., including in Ohio, the epicenter of the opioid epidemic, where about 46,000 people are currently behind bars.

Recognizing the potential of art to shed light on issues surrounding drugs and incarceration, this year, Fresh A.I.R. Gallery has sought artwork by currently and formerly incarcerated individuals whose lives have been affected by substance use. Select pieces were to be featured in a group exhibition at the gallery in July 2020. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic has altered these plans, both temporarily closing the physical Fresh A.I.R. Gallery space and making it more difficult for incarcerated artists to obtain needed art supplies and submit their work. We have decided to postpone the full exhibition until these issues can be addressed.

In the interim, we are pleased to highlight the artwork of the show's co-curator, Aimee Wissman, along with that of returned artists Whitney Johnson and Jayme Santini. The work of several currently incarcerated artists who were able to submit their work to us will be added shortly.

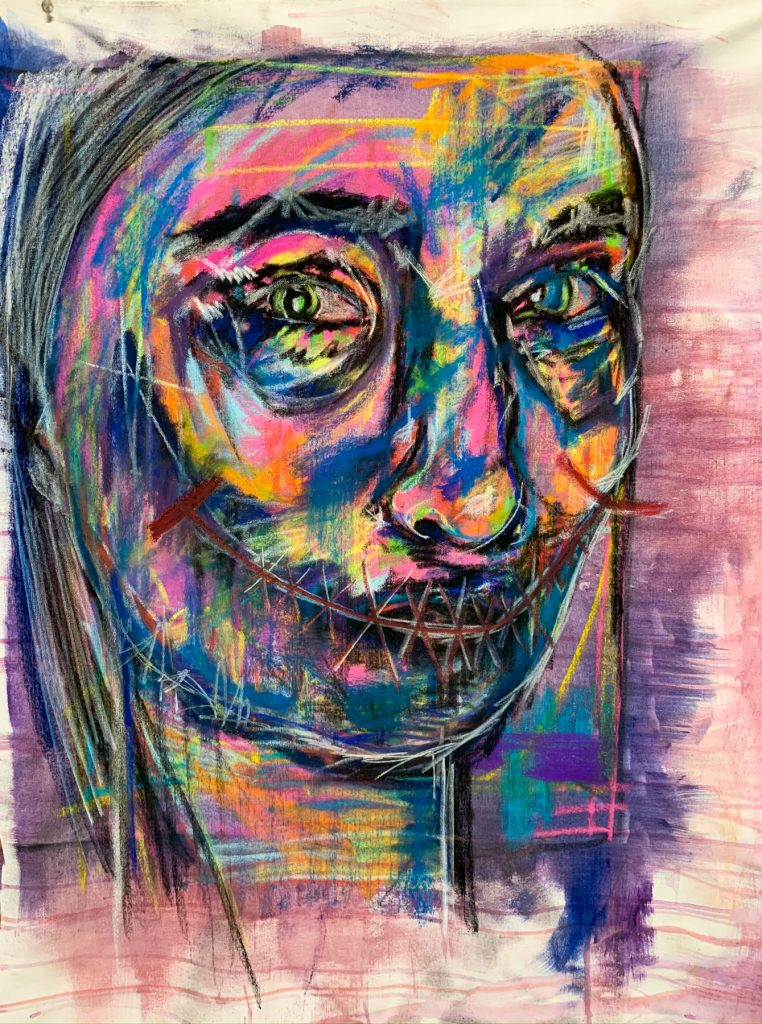

Aimee Wissman: Are Prisons Obsolete, self-portrait, 2020 (24 x 36", acrylic, ink, mixed media)

From Lauren Pond, Fresh A.I.R. Gallery Manager:

Last year, as Aimee Wissman and I first planned this group exhibit, we also brainstormed about a show title - something that, in addition to being thematic, might offer inspiration and guidance to participating artists. "What about Trust the Process?" Aimee suggested, noting that prisoners don't always have access to or use traditional art-making methods. That idea of embracing the act of creating – of encouraging artists to make whatever felt right to them, using whatever materials or approaches they had – became central to our call for entry. It's also central to Aimee herself, and to how she views her own artwork.

Aimee is a woman of many titles: visual artist, filmmaker, arts administrator, mother, student, and founder of the Returning Artists Guild. Incarceration is also part of her background. As a young adult, she served a five-year sentence at prison Dayton Correctional Institution. Prior to that, she'd spent a decade addicted to heroin, which had helped her suppress feelings of insecurity, she said. For her, the drug's physiological effects were especially powerful: Using it wasn't as much about getting high or leaving a situation as it was about feeling at home in her own body. In prison, however, opiates were no longer a viable option.

"I was in a place where I was going to have to look at myself. I was definitely going to be alone. I was not going to be able to have any of my familiar coping mechanisms," she said. "The environment was just so painful that I had to find something. I had to figure out how I was going to not harm myself or other people, essentially."

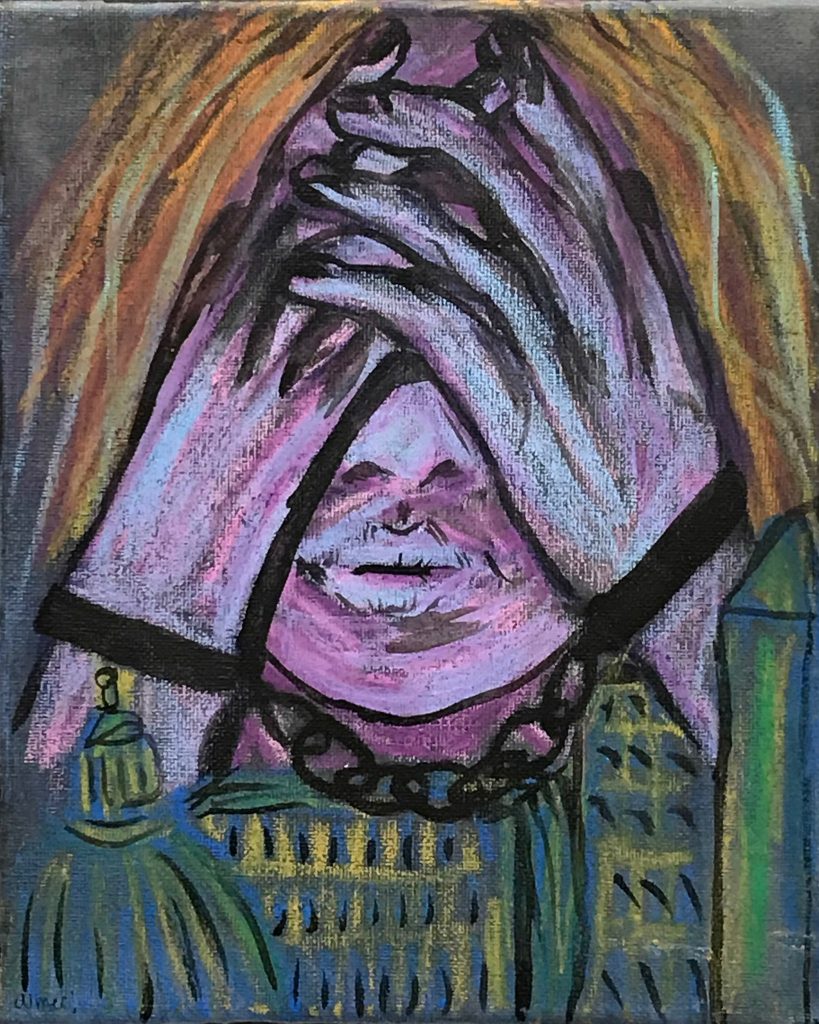

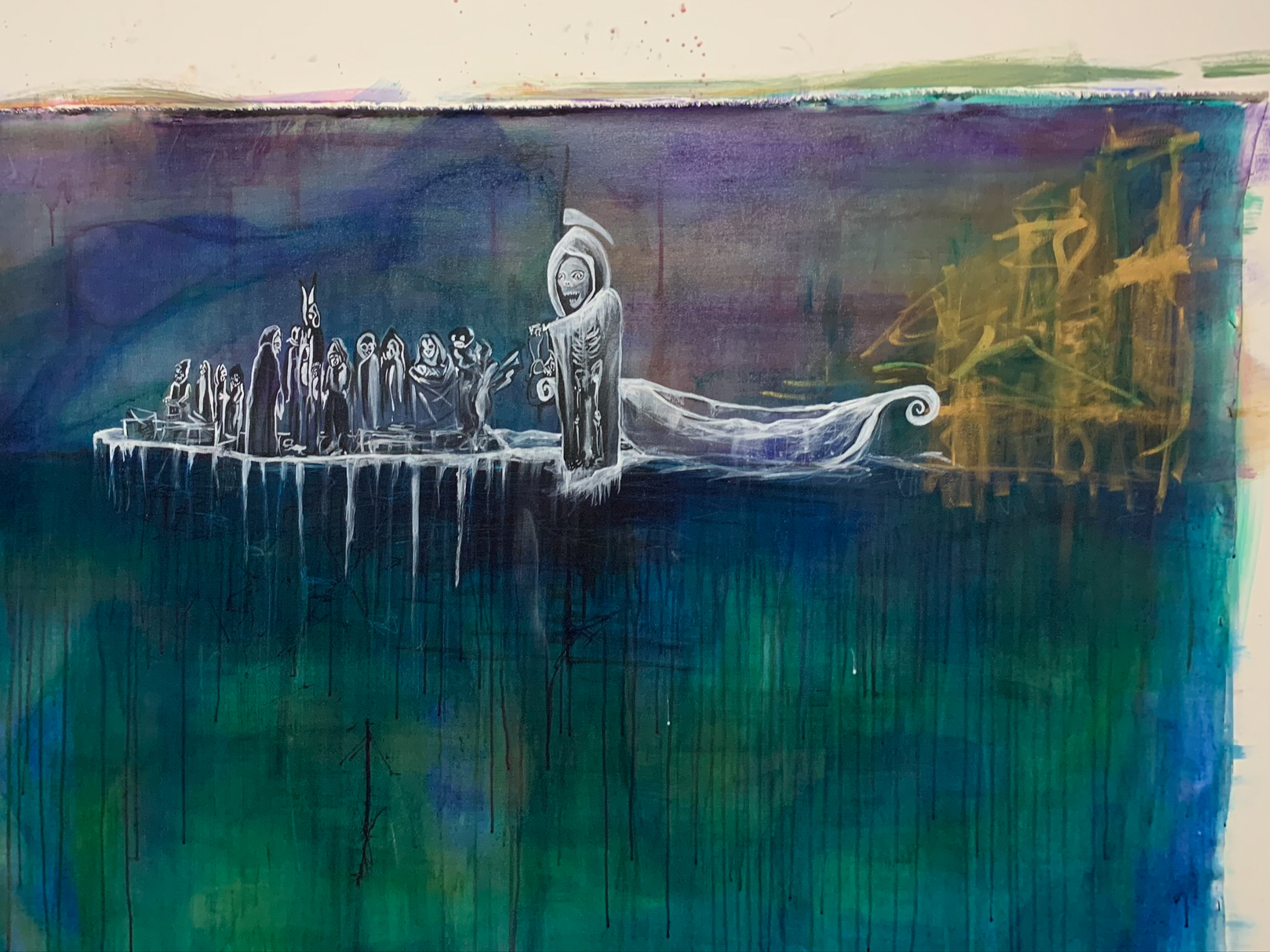

GOMI, the God of Mass Incarceration

That something was art.

Aimee started with journaling, using creative prompts and packets of writing guidance others would give her. Wanting to stay connected to her young daughter, she soon created cards and painted cups. She began using whatever materials she could find to make visual art, including styrofoam lunch trays from the prison cafeteria, which she cut up and dipped in paint to make her first print of a character called GOMI, or the God of Mass Incarceration. GOMI symbolizes a correctional system that's designed to sacrifice and devour society's unwanteds - addicts, the mentally ill, criminals - she said.

More versions of GOMI, as well as paintings, followed, and Aimee continued to lead an art therapy program inside of Dayton Correctional Institution.

Portraits of Black women killed by the police, inspired by the "Say Her Name" campaign

The Returning Citizen, a fish out of water, 2019 (48 x 36", ink, acrylic, and mixed media)

The Middleman, a wolf in sheep's clothes, 2019 (24 x 24", ink, acrylic, and mixed media)

The Good Cop, when pigs fly, 2019 (24 x 24", ink, acrylic, and mixed media)

But for Aimee, the most significant thing about art was – and continues to be – the creative process. Creating is of course an integral part of artwork, yet something that can be overshadowed, even hindered, by focusing on the finished piece: how other people will experience it, how they will or won't value it. Aimee's own work and story are a testament to the contrary: to the importance of letting go of those external ideas and expectations, and letting an artwork's value be in its very process and making.

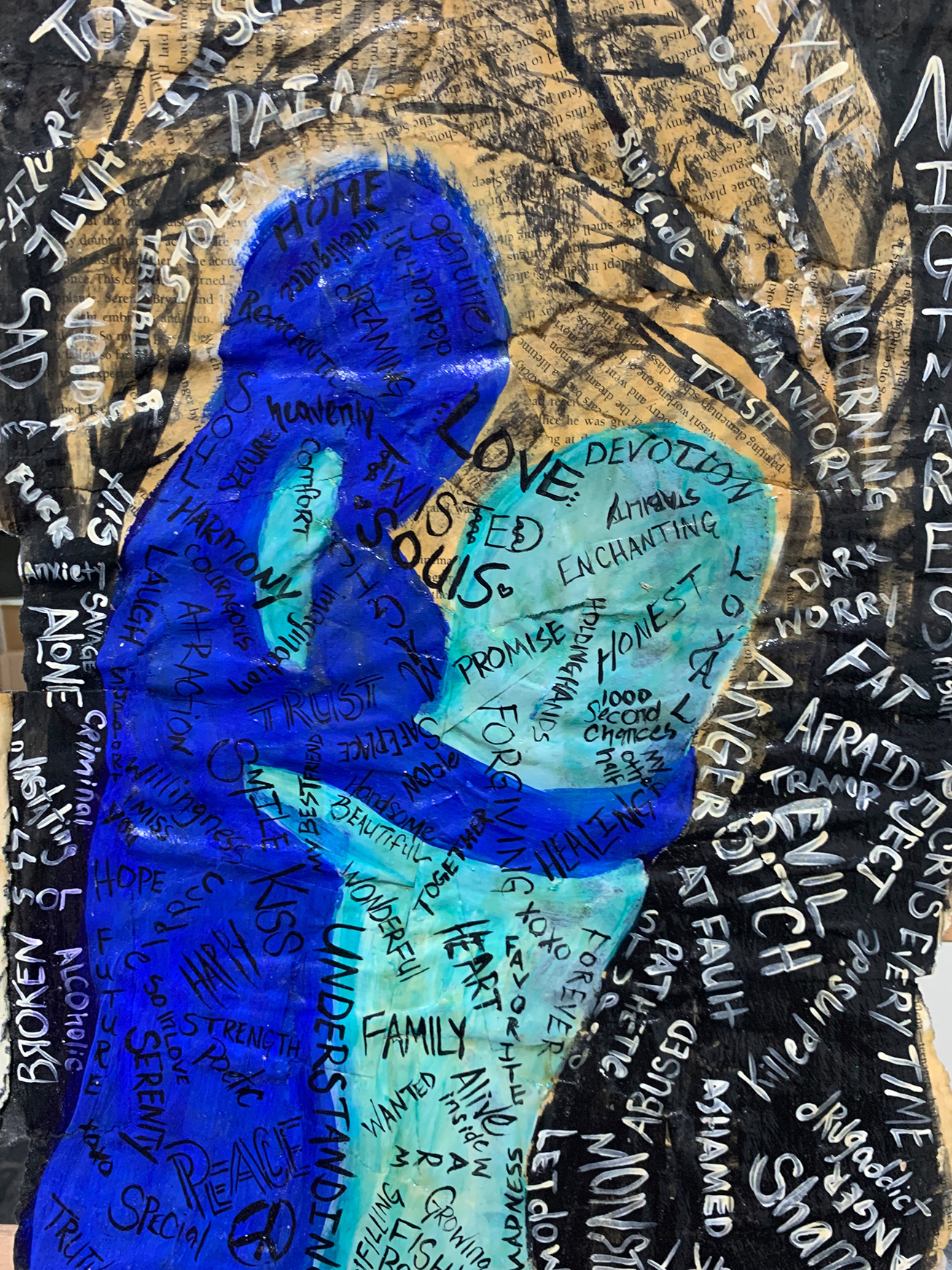

In prison, working in confined spaces with limited supplies, and without references or art historical information for guidance, she essentially taught herself how to be an artist – and developed self-assurance, resourcefulness, and a deeply layered style along the way. In many of her pieces, vibrant washes of color, markings, words, and characters accumulate on worn, sometimes previously used canvases.

"I have a real confidence in my ability to just work through the materials and struggle," she explained.

Her inner experiences likewise spill forth onto the canvas layer by layer in the cathartic act of creating. Aimee explained that art-making for her is also a form of mental and physical processing: a means to exorcise her insecurities and negative emotions, which in the past would have driven her to use heroin. It also helps her to feel at home in her body, to develop the self-love she once lacked. Without art, she doubts that she would be in recovery.

"It wasn't just like I'm repressing something by using a substance. I'm not avoiding it when I'm creating; I'm actually handling it, almost like material," she said. "I think there are parts of my life that were really, really hideous, and I needed someplace to just chew them up and spit them out."

Her Body is the Platform, The World in One Kitchen Sink (for Carole), 2020 (5 x 6', ink, acrylic, spray paint, chalk)

Listen to Aimee discuss this piece:

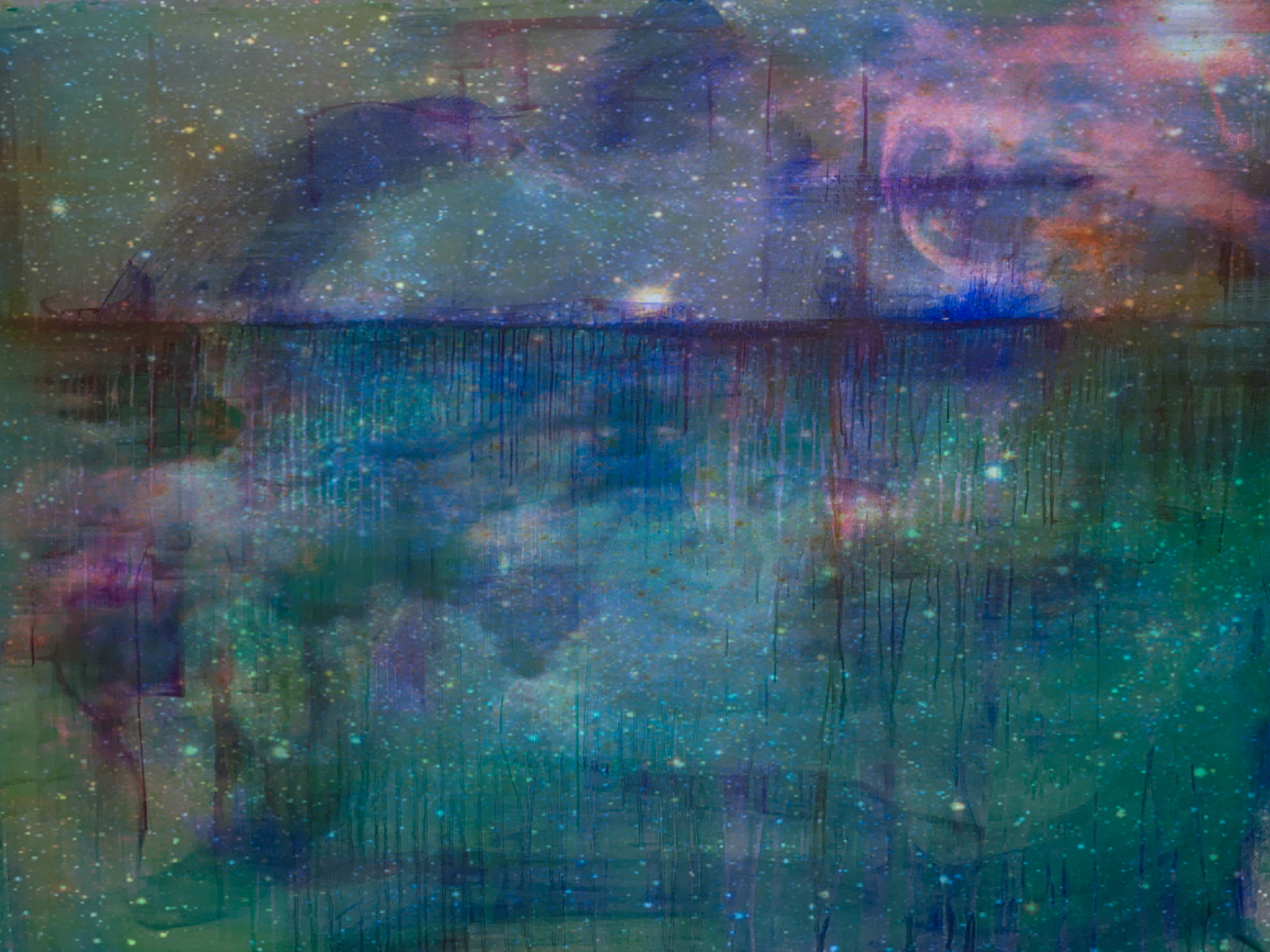

You bought the ticket, now ride the ride, 2020

(9 x 5', ink, acrylic, chalk)

Listen to Aimee discuss this piece:

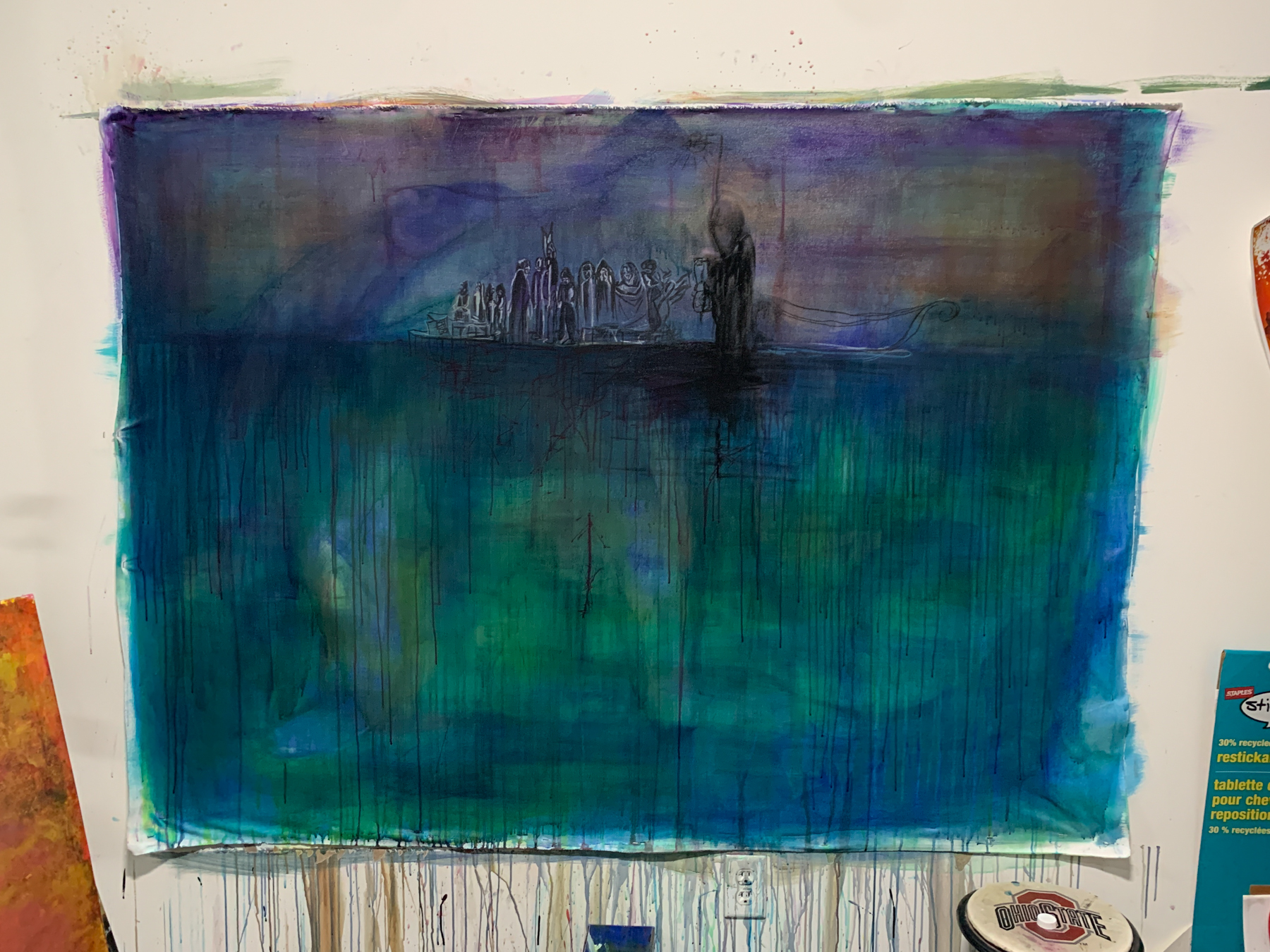

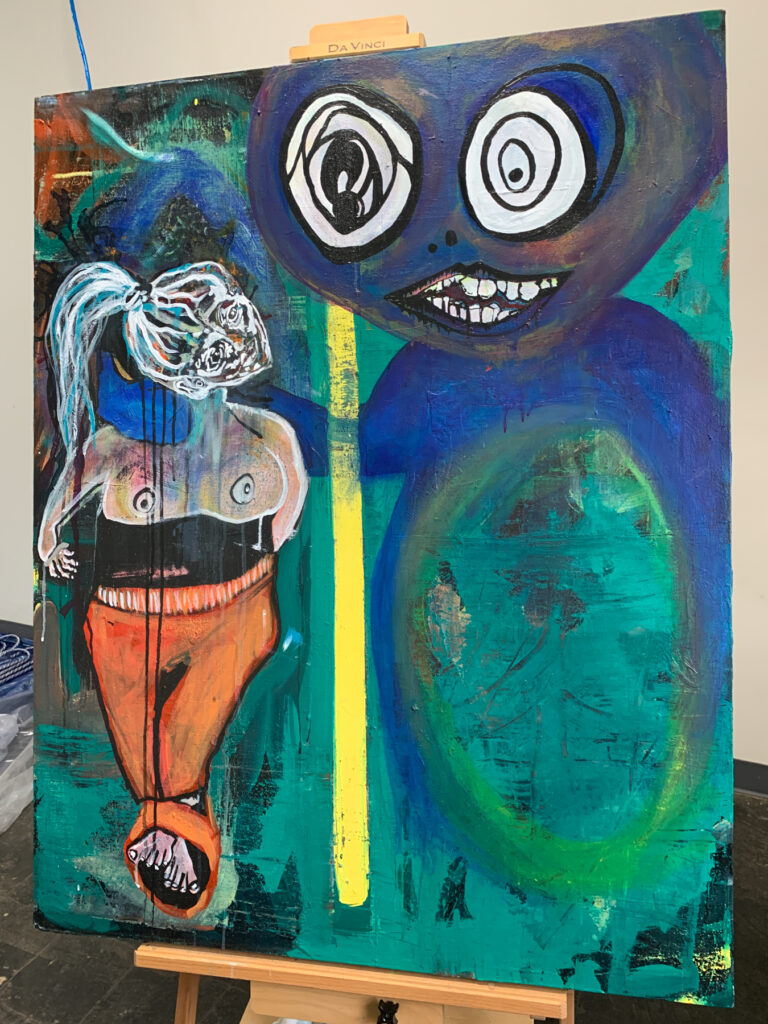

Sister You Gotta Put Yourself First, a girl and a GOMI, 2020 (3 x 4', ink, acrylic, chalk)

Listen to Aimee discuss this piece:

After her release from Dayton Correctional Institution, Aimee found herself confronting the numerous struggles of re-entry: finding safe housing, gaining custody of her daughter, trying to earn a living. Without art schooling or professional experience, she's also faced barriers in the art world. However, she has continued to create, gaining national visibility for her work and process, as well as encouraging other currently and formerly incarcerated artists in theirs.

"I've been really trying to figure out what it means to leave more than just an image or an emotion or a sale behind, but to really build a community around art and build a support system for the people that are coming behind me," Aimee said.

Read Aimee's artist statement

John

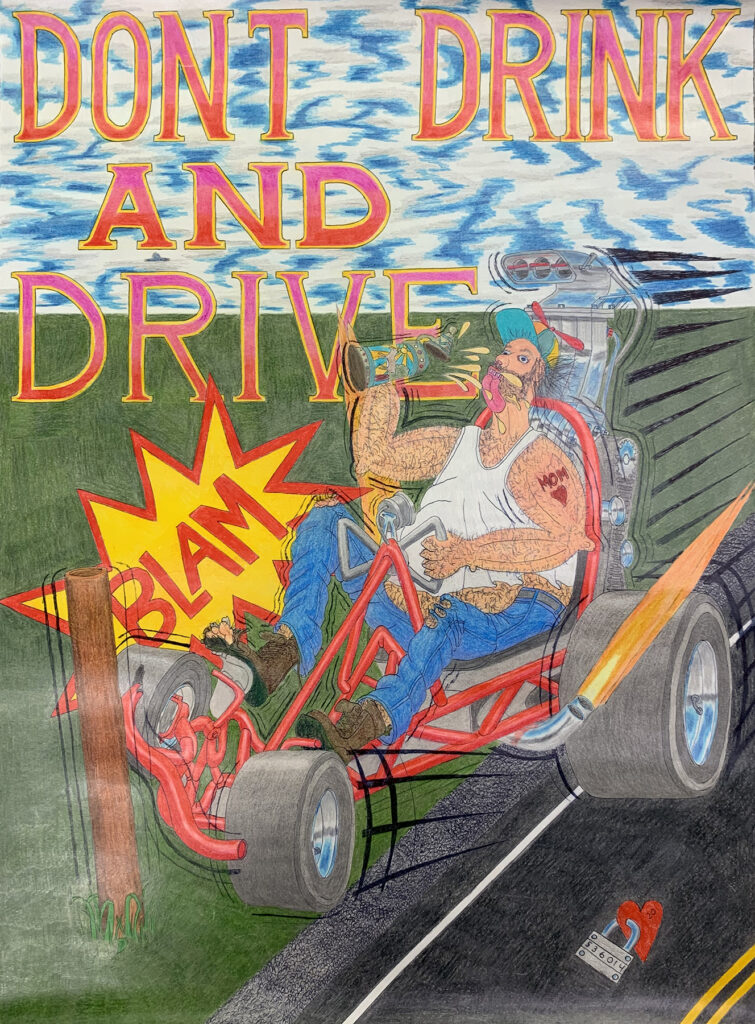

Don't Drink and Drive (24 x 18", Colored pencil on paper)

Raymond

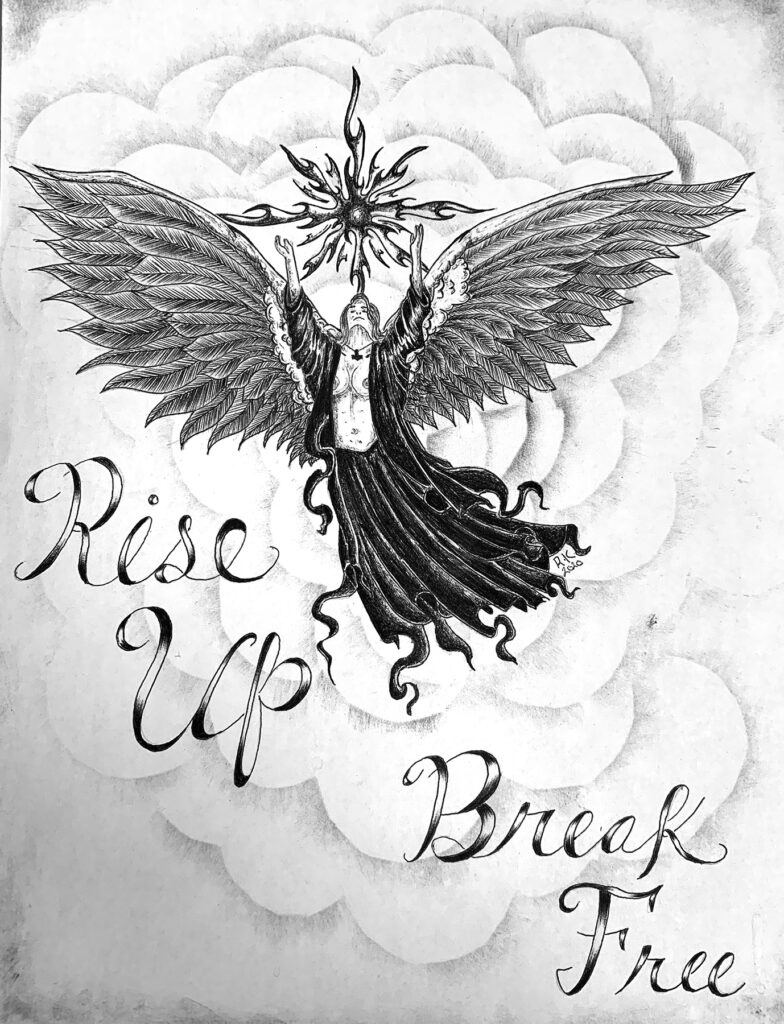

Rise Up, Break Free (11 x 8.5", Graphite on paper)

Whitney Johnson

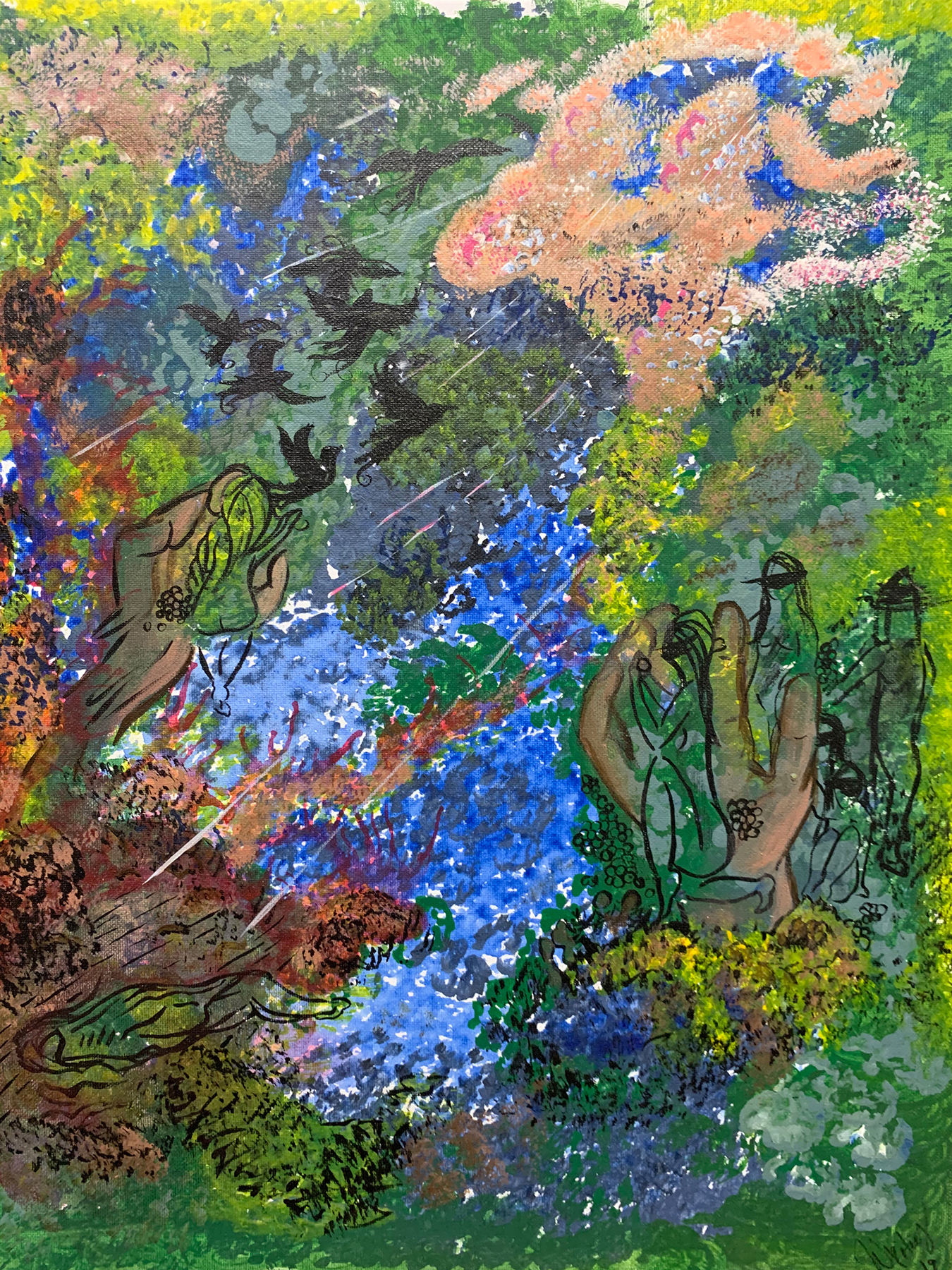

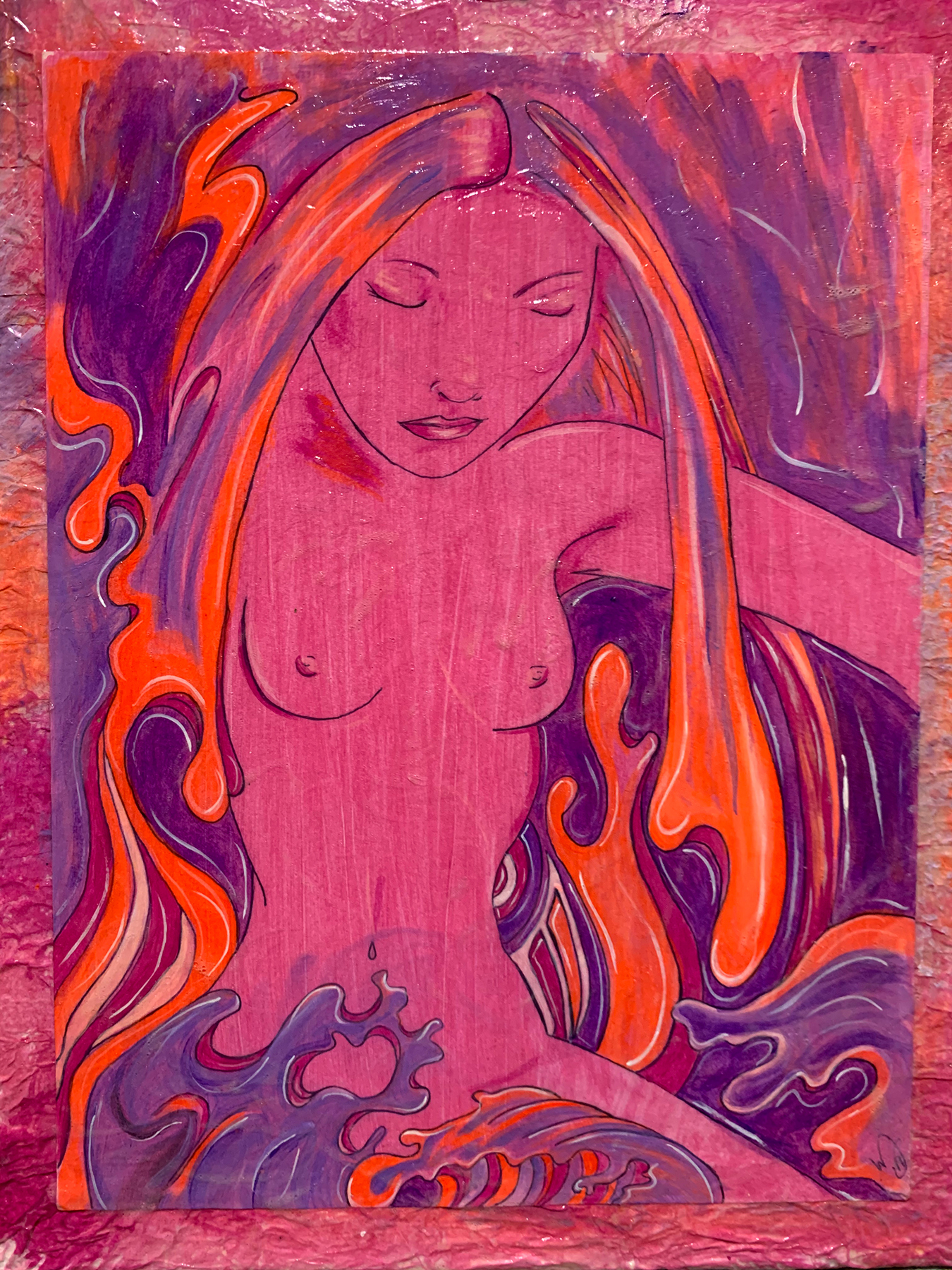

Morning Mercy, 2019 (18 x 12", mixed media)

Midnight Garden, 2019 (18 x 12", mixed media)

Introspection, 2019 (18 x 12", mixed media)

Soul to Squeeze, 2019 (18 x 12", mixed media)

Michael

Wishing Well Candy Dispenser (woodwork and mixed media)

Doll House Jewelry Box, View 1 (woodwork and mixed media)

Doll House Jewelry Box, View 2 (woodwork and mixed media)

Grain Mill (woodwork and mixed media)

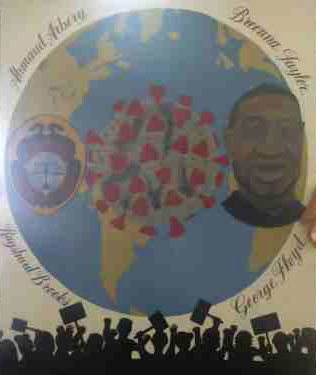

The World We Live In (painting)

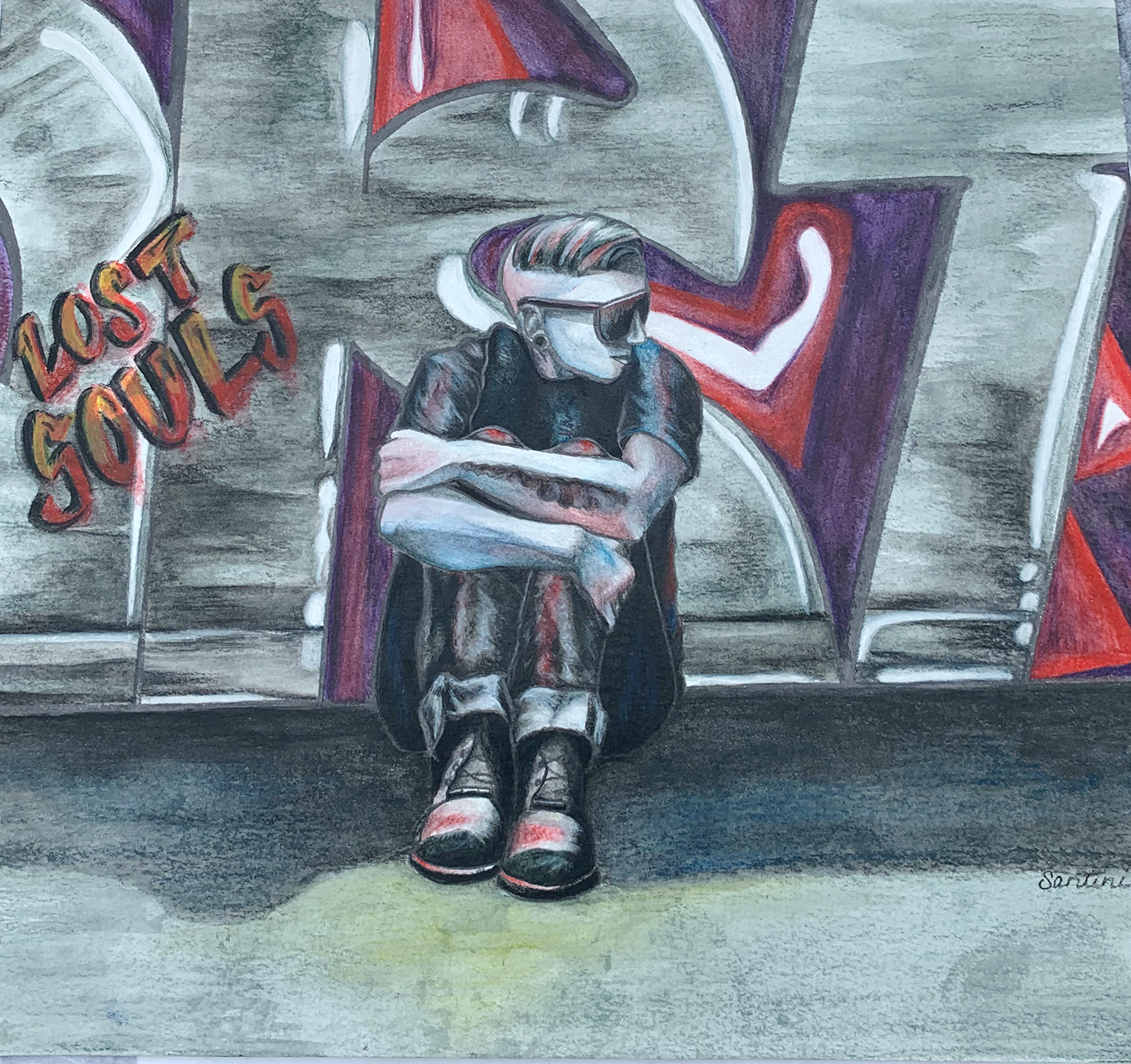

Jayme Santini

Lost Souls, 2019 (12 x 9", charcoal, colored pencil, watercolor)

Wasted Youth, 2019 (18 x 12", charcoal, pencil, colored pencil)

For further information about the artworks displayed, please contact us.